1841 words

Parent: T.00_ED_TEXTUAL HOLOGRAM: PRESENTATION

DIAGRAMS OF COEXISTENCE

Source: Elie During, « L'architecture du mouvement : Masaki Fujihata », in Anarchive n°6–Masaki Fujihata, Paris, Éditions Anarchive, 2016.

Voices of Aliveness, a stereoscopic projection shown at the Stereolux space in Nantes in summer 2012 (see link) pursues Fujihata’s long-term explorations launched with his “Field-Works” series. It all began with a participative performance. Over a period of several days, some sixty locals cycled along a circuit half a kilometre long, and were encouraged to shout, scream and sing as they did so. Each individual trajectory was recorded in two distinct ways: visually and aurally by a camera fixed to the handlebars (facing the cyclist, who was filmed face to camera), and topographically, by a GPS device. Fujihata then worked with a composer to organize these multiple events, free of any concern for linear order, into a multiplicity of elements in the form of image capture and video sequences along with geopositioning data. All this material was digitally converted into graphs on a relatively abstract spatial map, as Fujihata had already done in his 1994 Impressing Velocity–Mount Fuji. The goal was to give shape to the performative community that collaborated on the project by following one simple intuition: through their movement in space, participants would each inscribe something analogous to a voice on a stave. The implicit hypothesis was that the performance constituted a unique event, spread out in time, in which each trajectory embodied, so to speak, a particular projection or cross-section. The problem was how to depict this fragmented coexistence, a coexistence that the usual narrative structure with its succession of sequences is unable to grasp. The formal challenge entailed creating a space-time capable of totalizing the different lines without cancelling the singularity of each trajectory, jumbling them all together. One had to give form to the community of shouters in a distributive rather than collective way, thus avoiding to treat them as “a whole.”

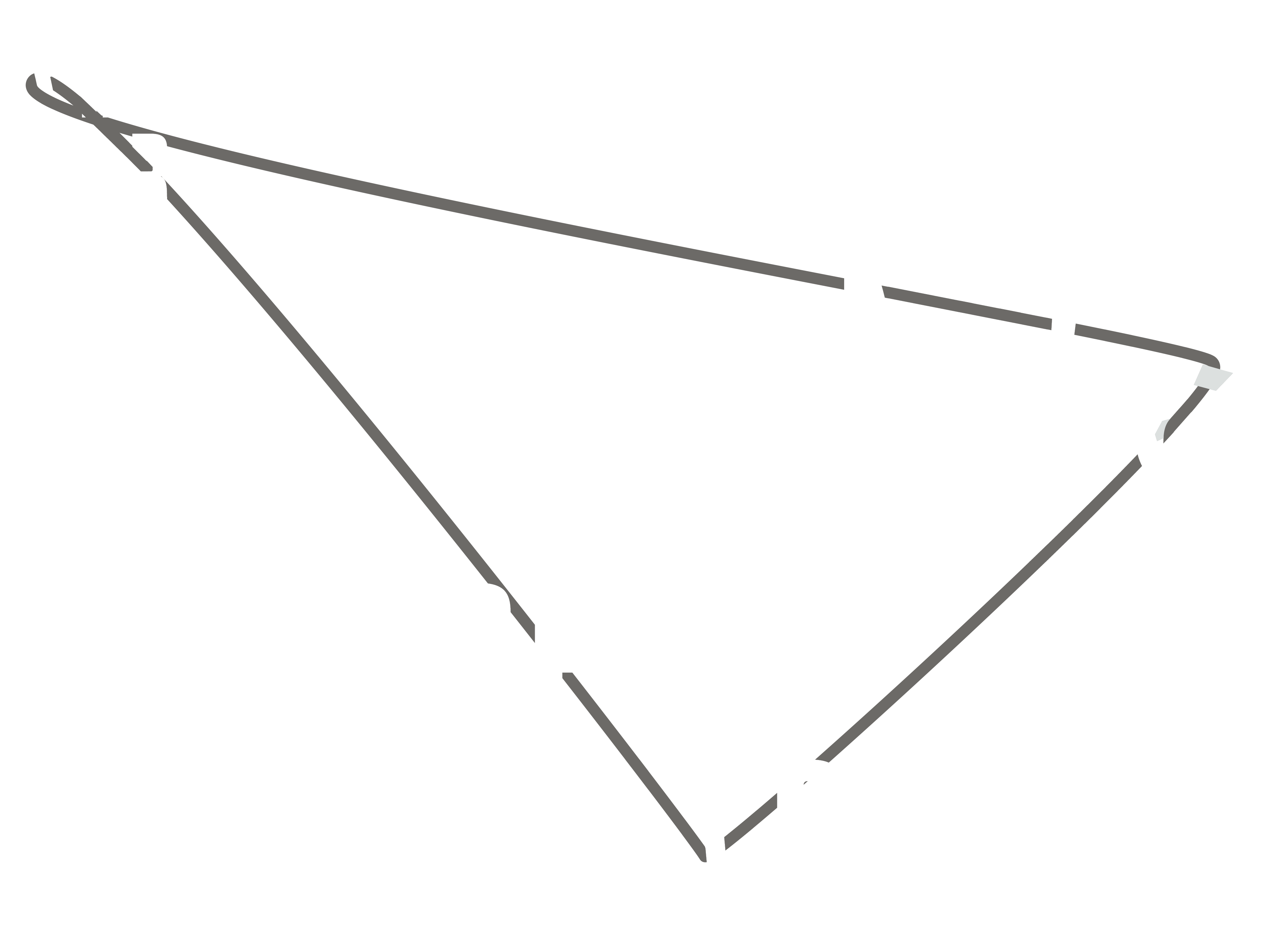

In doing so, Fujihata did not try to deconstruct the event, or to artificially elicit a perceptual equivalent through simultaneous projections or mobile viewers. His aim was rather to compose a virtual event which, strictly speaking, no one had actually experienced, since the trajectories whose polyphonic coexistence had to be organized actually occurred sequentially. Fujihata therefore started by immobilizing and placing the viewer: the viewer is connected to the installation via polarizing glasses, and is encouraged to navigate through the stereo imagery by working a rotating disc on a base. From the outset, artificial perception makes a naturalistic reconstitution of the event’s space-time impossible. At the same time, it blurs the usual coordinates of videographic experience. Indeed, at first the screen simply shows white lines against a black ground—a multiplicity of tortuous, looping paths. They represent traces of various circuits superimposed so as to form a kind of tower (Fujihata refers to a “meta-monument”). This evolving graph-like object is generated by the composition of movements in virtual space; Fujihata mentions the height it would have if it were actually built full-scale (360 meters). He is already planning to produce a sculptural version of this piece with 90 layers, yielding a model of the monument that would be almost four meters high. But this media-generated structure, obtained by compressing layers of space-time, would be no more than a graphic exercise if it did not incorporate, scattered here and there on different lines, a multitude of videographic animation cells, lighting up in random order.

When activated, these cells or screens punctuating the timelines trigger a video sequence corresponding to the part of the trajectory on which they are located and along which they advance. Just as a parameter describes the twists of a curve, the intermittently triggered sequences describe sections of the trajectory. Paradoxically, the flashing stream of simultaneous images renders an overall, synoptic grasp impossible: in this state of perpetual animation—which evokes the concept of the impermanence of things (mujo) within the flow of time—nothing ever coheres into one “big picture.” And yet something like an overall form seems to take shape before our eyes. As Fujihata says, although it is almost impossible to become absorbed in contemplating two screens at the same time while maintaining the perspectival illusion that makes each one like a veduta—or window overlooking three-dimensional space—, it is possible to experience two (or even several) “flat” images arranged in the same space. That is where stereoscopy comes in: the imperfect convergence of views strangely unfolds space between the flat video cells rather than presenting these as cross-sections of a pre-given space.

This inevitably bears comparison with the Japanese concept of ma as interpreted by some contemporary architects: a space/time (or time/space) that unfolds between things via combinations of multiple temporal axes and planes (see Arata Isozaki, “Ma – Space/Time in Japan”). In Voices of Aliveness, the composition of disjointed planes is scaled up to the entire installation. While allowing the viewer to move within the image, the work keeps the level of interaction to a minimum. It prevents the beholder from yielding to the immersive reverie encouraged by the enveloping atmosphere of a darkroom; on the other hand, it prevents the projection screen—what Jean-Louis Boissier calls the “hyper-screen—from functioning like a frame. (See Jean-Louis Boissier, “Le linéaire actif” (link), and Lev Manovich, Software takes command, 2008 (link, Creative Commons license), both accessed February 2015).

In fact, there is no space to frame—if by space we mean an analog of the three-dimensional space organized in depth according to the laws of perspective. The space reconstructed stereoscopically here is a virtual space, or more accurately an abstract space similar to the configuration or phase spaces contrived by physicists when representing the coexistence of multiple lines of development—real or simply potential—combined with the relative velocities of one or several material systems. This kind of abstract space comes into play as soon as one has to deal with spatio-temporal perspectives in the form of temporal sequences or mobile cross-sections. Cinematic architectures require diagrams. And the stereoscopic projection of Voices of Aliveness is primarily just that, a diagram of animated space-time, with the twofold attention allowed by all diagrams of this kind: each trajectory can be followed locally, as it unfolds, along with the moving images that intermittently animate it (focused attention), and at the same time can be apprehended more abstractly on the plane of coordination where all trajectories coexist (diffuse or distributed attention), according to global diagram ideally deployed in 4D but in reality perceived in pseudo-3D (stereoscopy).

There is of course a hidden perspective behind each trajectory—the perspective of the artist who traces and materializes the shifting points of view by organizing their simultaneous deployment in a virtually composed space. We might gloss this ubiquity by asking, like Gilles Deleuze, whether the model replacing classical perspective here is like a divine gaze looking down on its creation, or rather like an omniscient “reader” able not only to follow things simultaneously along every line of development, but to do so in “real time” as each unfolds from moment to moment (Gilles Deleuze, The Fold, p. 82–83). But for space to function as a map or a diagram, it is of course crucial to present the videographic cells as flat images—two-dimensional surfaces—rather than as windows opening onto the world (or worlds). Failing that, perspectival illusion will inevitably return. This is where mobile screens prove crucial: for they will no longer function as a window once their movements are perceived as such (besides the virtual camera movements within each shot). This was Fujihata’s key innovation, which prompted Jean-Louis Boissier to say that the artist set what might become a new standard for video art and perhaps the movies. Indeed, Fujihata managed to combine the video recording of each trajectory and its associated geolocation data with the recording of the actual movements of the camera in the space of the performance where the various shots were taken. A close look reveals that each screen is supported by a wiry, pyramid-shaped structure delineating a small field of projection. These digital pointers combine the virtues of a magnetic compass and an accelerometer, and thanks to them the final installation literally reproduces the varying camera angles via the rotating movements imparted to the screens as they move along the trajectories. Each mobile cell thus displays not only the recorded sequence (seen on both sides) but also the point of view from which it was recorded. These shifting angles amount to staging point of view as such—or point of view as form, to quote Boissier once again. This unusual cinematic approach retains a traditional iconic function (by mimicking the real movements of the camera in 3D space), but all this happens in a space that is nevertheless diagrammatic throughout. And once the view shifts and shows the other side of the image, or when two shots collide—sliding over one another or gently merging—we exit the analog or representational mode and cross a new threshold of visual organization.

Fujihata himself theorizes this situation by identifying logically ordered degrees of formal objectivation: vision—perception or mental representation—is the first degree, beyond which images recorded and projected in movie or video form are the second degree. But there also exists a third degree of objectivation, corresponding to the formal elaboration of the point of view itself, a viewpoint liberated, so to speak, from the constraints of situated vision. Fujihata implements this degree through the arrangement of mobile screens seen frontally or at an angle, and above all by their movement independent not only of the content in the shots but also independent of the views embodied by concrete observers (the participants in the original performance, on whom the cameras are trained at all times). This third level of cinematic objectivity leads to a totally new type of experience of viewpoint, somehow placing the viewer behind the observers who supposedly occupied those points of view (even when they are shown frontally, as here). This approach echoes the formal, polyphonic or “vertical” time that Gaston Bachelard associated with the dimension of simultaneity, contrasting it with the continuous flow of duration, the successive presents endlessly receding into the past (see The Dialectic of Duration, “Temporal Superimpositions”). It is a matter of occupying several points of view simultaneously, or rather of viewing them jointly from no fixed position. Perspective is not exactly abolished, but turned inside out. All that remains of it is Fujihata’s mobile diagram. This is how the architecture of movement is constructed—by circumventing the third dimension.

Links

︎ egs.edu/biography/elie-during ︎ parisnanterre.fr/m-elie-during--697698.kjsp

From the same writer

T.00_ED_TEXTUAL HOLOGRAM: PRESENTATION T.01_ED_FOLDS AND PIXELS T.02_ED_DIGITAL SUBLIME T.03_ED_MATHEMATICAL SUBLIME T.04_ED_IMMANENT SUBLIME T.05_ED_NEXUS T.06_ED_KINKED CLASSICISM T.07_ED_LOOSE COEXISTENCE T.08_ED_FLOATING TIME T.09_ED_FLOATING SPACE T.10_ED_RETRO-FUTURES T.11_ED_EXITING VIRTUAL REALITY T.12_ED_BULLET TIME T.13_ED_GHOST TIME T.14_ED_SUBLIMINAL TIME T.15_ED_DIAGRAMS OF COEXISTENCE T.16_ED_VOLUME-IMAGE T.17_ED_VERTICAL TIME T.18_ED_TURNING MOVEMENTS T.19_ED_SUPERTIME T.20_ED_PROTOTYPE T.21_ED_ZERO-G ARCHITECTURE T.22_ED_SHOCK SPACE T.23_ED_TRANSPARENCY